Few conceptual artists have had the staying power of John Cage (1912-1992), whose work and reputation needs no introduction from myself. But, come to think of it, there are a lot of ways to introduce Cage to others, and to one's self, and too many of his own philosophical ideas and other people's notions on the "What It Is" of his pieces mainly serve to get in the way of natural musicianship. The fastest way to hear a poor recording of a composer's work is to focus on their earlier pieces, before their artistic sensibilities had crystallized, and listen to well-meaning interpreters over-idea things - that is to say, applying an idea later realized to a piece written before the idea had physical examples. I've heard too many recordings of The Rite of Spring and Petrushka that assume all of Stravinsky's works should to be played mechanically and with hair-width staccatos. This problem is exponentially applied in the case of Cage, and Quest (1935) is a fine object lesson.

(Click for larger view)

Quest was actually written as the second movement of a larger work, the first one supposedly for "various objects" (a link to pieces like Living Room Music), but that initial movement is lost. Quest was written at the tail end of Cage's apprenticeship under Schoenberg, a time when Cage almost literally worshiped the man and was still quite unsure of his own voice. Cage admitted that he had no inner ear for harmony, a fact all his compositions share, and Schoenberg told him that dealing with this problem would be like "coming to a wall through which he could not pass." Cage later recounted that the most Schoenberg did for him was to reaffirm his resolve to write music, and how to live fully as a composer. It's evident from this piece that none of Schoenberg's techniques rubbed off on him, as I would think more of Dane Rudhyar as a reference point. Rudhyar was a singular philosophical entity, and used the piano as a "symphony of gongs" to craft cathartic, thunderous, improvisational works on cosmic themes. Rudhyar made a point of leaving harmony up to intuition rather than system, and Cage's approach to free atonality has some striking similarities to Rudhyar's (specifically in bars 7 & 14, with vaulting melodies over rich harmonic bases). The open fifths and title also allude to a mystic space. As with many works by young composers the piece takes radical turns in character and material very quickly, so a performer with good dramatic and textural sense is required to make it work. Unfortunately, the only YouTube recording I could find is rubbish.

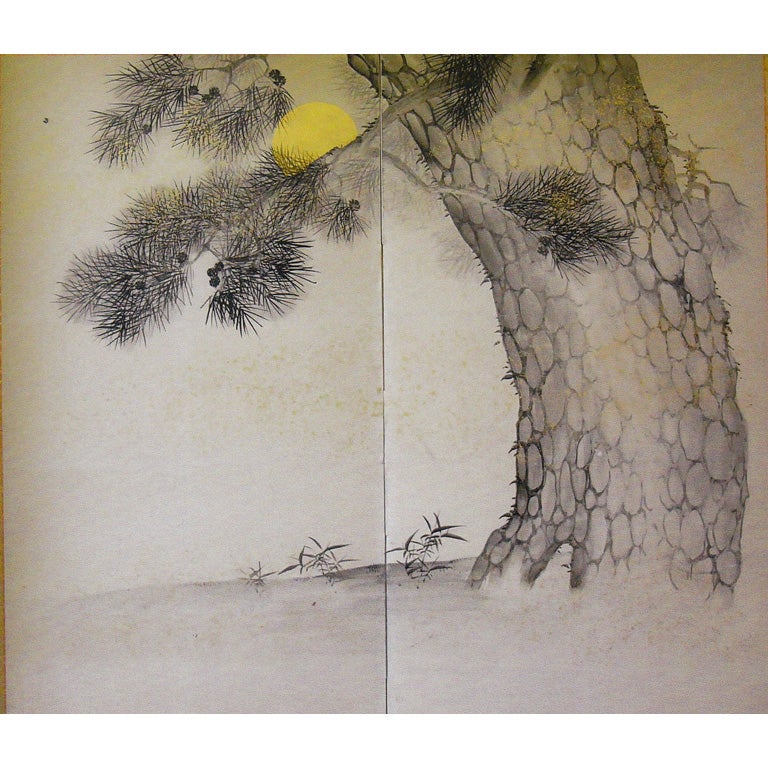

It's not so much that there are wrong notes or rhythms, but it's more that there's no sense of pacing, line, arc, or atmosphere, and when given a piece with no tempo marking you should try to make a meal of the thing. I'll never understand the impulse to play Cage's pre-I-Ching works with no sense of drama or texture (such as this recording of his 1933 Clarinet Sonata, which imagines all notes as being in different rooms from one other). I know that Cage never had much interest in deep harmonies, but it'd be nice to at least savor what he gave us. In case you're wondering there are better performances out there, and I'll look forward to the day they get uploaded. As a palette cleanser I've included an excellent performance of Bacchanale (1940), Cage's first major work for prepared piano, by Margaret Leng Tan, one of the few performers to nail the dramatic qualities of Cage's music. Bacchanale is a fine introduction to the dry, nocturnal world of the prepared piano Cage cultivated, reminiscent of a Hiroshige print of the Moon through pines (if such a print exists). Here's to eternal quests, mine and yours included.

~PNK

P.S. I found one!

No comments:

Post a Comment