Pedagogical music is great - it's necessary, accessible and has attracted the work of big name composers from across the ages. The only catch is that, because much of it is simple by design, people who are famous primarily for their pedagogical work, such as Aleksandr Grechaninov, see their other works neglected because audiences don't expect their stuff to be up to "concert" standards. Case in point: Dmitry Kabalevsky (1904-1987), one of the most famous Soviet composers of all time and one of a scant handful to see their work imported to the US back when we thought that was A-O-K (the '30's and '40's). Known for his third Piano Concerto and his ballet suite The Comedians, Kabalevsky's most commonly-played stuff are his easier piano pieces, such as the first piano Sonatina and his Variations in D, both of which have been in countless piano collections in the last several decades. These works are unchallenging for mainstream audiences, not only for their technical ease but also their pleasant Neoclassical language which was forced upon Kabalevsky by Stalinist compositional policy. Most of Kabalevsky's work is similar in tone if not technical difficulty, but one can find more adventurous stuff if they dig a bit deeper. My favorite work of Kabalevsky's is one of these alluring few and was written very early in his career, back in the twilight of the hayday of Soviet modernism before the clamps came down.

The Four Preludes, op. 4 were written between 1927 and 1928, the last couple of years before the end of a glorious era in Soviet arts administration that can best be described as a virtuosic free-for-all. Guys like Roslavets, Mosolov, Lourie and many more really did whatever the hell they wanted in the name of modern music, and it all came crashing down because Stalin and the new, Proletarian-minded arts boards new just enough to be wrong. Thankfully Kabalevsky wasn't gulag'd and his works have been preserved, such as these warmly experimental miniatures. The first two are leaf-like so they get the spotlight today, and they're also wildly different from each other. The first has a precious, childlike melancholy about it, the compact simplicity of the main motive contrasted against aching, chromatic chord undulations in the B section. This section is a fine example of how tonality can be bent nearly to breaking without sacrificing a good melody/harmony relationship. The second prelude is almost an etude, a fleet and lovely parallel fourths exercise and showcase for extended modal harmony. I'd be tempted to add a subtitle about ocean spray or flying, especially because of the excellent decision (either by Kabalevsky or the editor) to add ritenuti here and there to give the impression of sharp swaying. The other two preludes are a bit longer than these, but because I'm feeling generous (especially after coming off of a spectacular evening performing with my chamber group Cursive) I'll toss in the other two preludes free of charge.

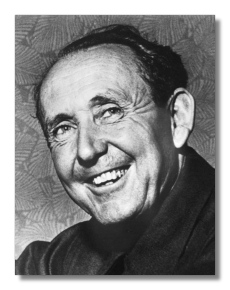

That last one especially sounds quite modern for the time, though not dissonant - makes me think of a wine festival or cottonwood fluff. Here's a fine recording of the set by Alexandre Dossin, a pianist I had the pleasure of seeing live at UPS many years ago.

~PNK