I used to frequent a record store in Tacoma, WA called House of Records, which boasted some impressively overstuffed racks of all genres and times. I especially liked riffling through the "20th Century Classical" rack, as it was a blitz of disorganized, mostly obscure items of not only recognizably classical artists but also plenty of odd 'tweeners with nowhere else to go. These lonely discs were $2 a pop unless otherwise marked, and I snagged a number of fascinating items, most notably a number of records with "KRAB" written across them with a black marker. At first I thought it was somebody's name, or at least a nickname, and I remember thinking to myself, "Man, this Krab guy sure had an interesting record collection!" It was interesting, a mixture of Avant-Garde jazz, classical, world music and experimental, none of which I'd heard of before but all of which beckoned my ears. As it turns out the Krab in question was really KRAB, a defunct Seattle FM radio station that I'm not old enough to have witnessed live. Founded in 1962 in an old doughnut shop building, the listener-supported station was an experiment in free-form programming, allowing a passle of young eccentrics to broadcast whatever they thought was interesting, resulting in an eclectic, commercial-free mix of genres with unique announcers in the mix. And in an unconventional turn of events the founding of the station also saw an odd little gift from a local composer.

(Click for larger view)

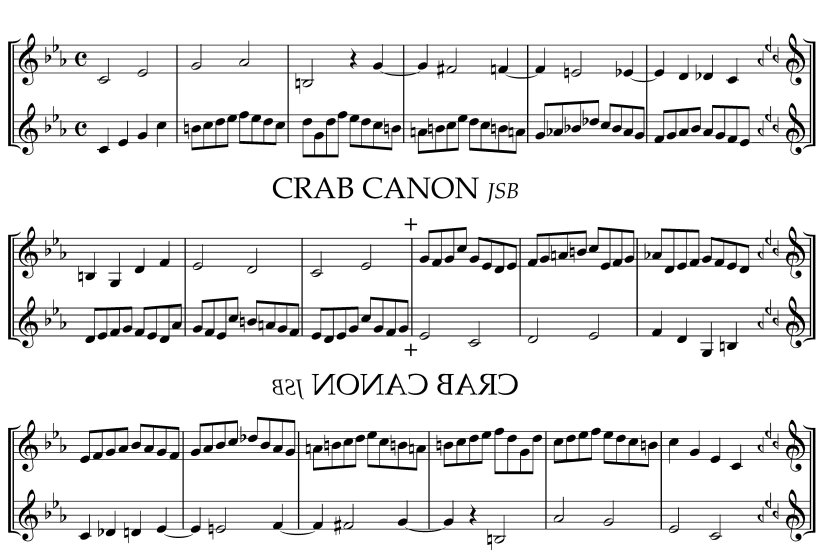

Luckily for those who don't care I don't know much about Henry Leland Clarke. He got his degrees at Harvard and ended up teaching at the University of Washington in his later years, retiring Professor Emeritus in 1977 at age 73. He was a member of the Composer's Collective of New York, a group dedicated to making songs for the working class, and worked under the pseudonym J. Fairbanks. He was also a member of the American Composers Alliance, certainly the only organization to publish something like this, and I can't pass up any chance to link to them as per my undying love for their work. I certainly didn't seek out any of his work; I came across this piece by happenstance while looking for works for voice and violin at the UW music library. The Puget Sound Cinquain may not actually be for violin, as it doesn't state that on the score and I have no other information on the piece than what's in front of me. Either way, it's labeled "Crab Canon for KRAB", and it's 1962 date of composition tells me that it my have been written as an inauguration piece for the station. Another issue is that it isn't actually a crab canon. A crab canon is a Baroque form of imitative counterpoint (two voices where the second imitates the first and its entrance is staggered), where the piece repeats itself in an inverse retrograde version at the halfway point while still sounding like a piece of music. I've also seen examples where if you simply turn the page upside down it looks identical to the right-side up view. Here's an example of the former from Bach:

(Click for larger view)

If you'll notice in Clarke's version, the lower line does retrograde in the middle, but that has no effect on the upper line, which is just an iteration of the subject. Even if it isn't a crab canon per se, it is a cinquain, a brief poetic form inspired by Eastern forms such as Japanese haiku and pioneered by Adelaide Crapsey. The criterion is a stanza of five lines with a stress order of 1, 2, 3, 4, 1 and a syllable order of 2, 4, 6, 8, 2. The cinquain here, written by the acutely obscure Wallace Bartholomew, follows that form nicely:

A bit

Of the ocean

That wandered far inland

Became entranced and decided

To stay.

It's a nice little picture of Puget Sound which fits in brevity and cuteness Clarke's music. Sidestepping modernism entirely, the quasi-canon sings in a clear-eyed E-major, meeting a charmingly simple poem with charmingly simple music. Violin would be an obvious choice for the lower line, creating an atmosphere of acoustic intimacy as if the performance is taking place on a back porch. I'd be interested to see the piece done by one person on both lines, perhaps as an encore to a grassroots concert. I'd be curious to know how this piece was fit into a KRAB broadcast, or if it was ever broadcast, or practically any other information on its genesis or legacy. Does anybody know about it? Anybody? Either way, it's a lovely miniature that I'd record myself if I had a violin. In the meantime, here's a beautiful, entirely different piece for voice and violin I was reminded of looking at the Cinquain, a folksong arrangement by the New Englander Howard Boatwright:

~PNK